When Security Researchers Pose as Cybercrooks, Who Can Tell the Difference?

A ridiculous number of companies are exposing some or all of their proprietary and customer data by putting it in the cloud without any kind of authentication needed to read, alter or destroy it. When cybercriminals are the first to discover these missteps, usually the outcome is a demand for money in return for the stolen data. But when these screw-ups are unearthed by security professionals seeking to make a name for themselves, the resulting publicity often can leave the breached organization wishing they’d instead been quietly extorted by anonymous crooks.

Last week, I was on a train from New York to Washington, D.C. when I received a phone call from Vinny Troia, a security researcher who runs a startup in Missouri called NightLion Security. Troia had discovered that All American Entertainment, a speaker bureau which represents a number of celebrities who also can be hired to do public speaking, had exposed thousands of speaking contracts via an unsecured Amazon cloud instance.

The contracts laid out how much each speaker makes per event, details about their travel arrangements, and any requirements or obligations stated in advance by both parties to the contract. No secret access or password was needed to view the documents.

It was a juicy find to be sure: I can now tell you how much Oprah makes per event (it’s a lot). Ditto for Gwyneth Paltrow, Olivia Newton John, Michael J. Fox and a host of others. But I’m not going to do that.

Firstly, it’s nobody’s business what they make. More to the point, All American also is my speaker bureau, and included in the cache of documents the company exposed in the cloud were some of my speaking contracts. In fact, when Troia called about his find, I was on my way home from one such engagement.

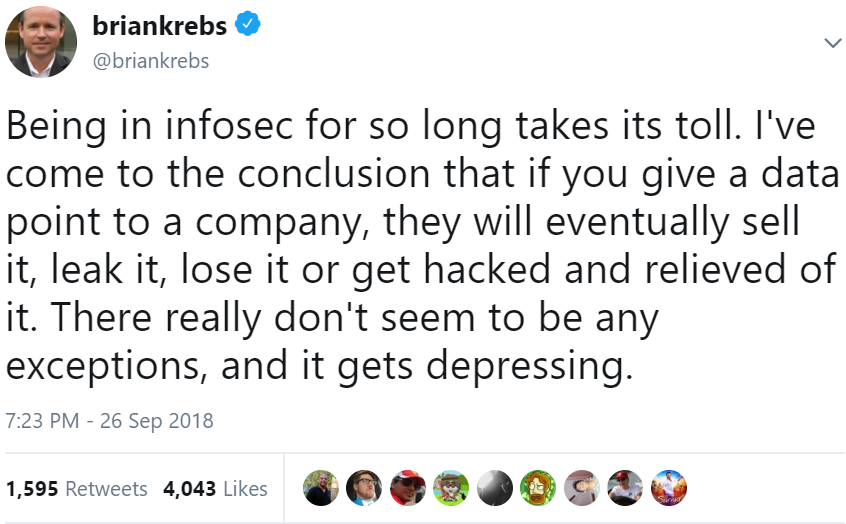

I quickly informed my contact at All American and asked them to let me know the moment they confirmed the data was removed from the Internet. While awaiting that confirmation, my pent-up frustration seeped into a tweet that seemed to touch a raw nerve among others in the security industry.

The same day I alerted them, All American took down its bucket of unsecured speaker contract data, and apologized profusely for the oversight (although I have yet to hear a good explanation as to why this data needed to be stored in the cloud to begin with).

This was hardly the first time Troia had alerted me about a huge cache of important or sensitive data that companies have left exposed online. On Monday, TechCrunch broke the story about a “breach” at Apollo, a sales engagement startup boasting a database of more than 200 million contact records. Calling it a breach seems a bit of a stretch; it probably would be more accurate to describe the incident as a data leak.

Just like my speaker bureau, Apollo had simply put all this data up on an Amazon server that anyone on the Internet could access without providing a password. And Troia was again the one who figured out that the data had been leaked by Apollo — the result of an intensive, months-long process that took some extremely interesting twists and turns.

That journey — which I will endeavor to describe here — offered some uncomfortable insights into how organizations frequently learn about data leaks these days, and indeed whether they derive any lasting security lessons from the experience at all. It also gave me a new appreciation for how difficult it can be for organizations that screw up this way to tell the difference between a security researcher and a bad guy.

THE DARK OVERLORD

I began hearing from Troia almost daily beginning in mid-2017. At the time, he was on something of a personal mission to discover the real-life identity behind The Dark Overlord (TDO), the pseudonym used by an individual or group of criminals who have been extorting dozens of companies — particularly healthcare providers — after hacking into their systems and stealing sensitive data.

The Dark Overlord’s method was roughly the same in each attack. Gain access to sensitive data (often by purchasing access through crimeware-as-a-service offerings), and send a long, rambling ransom note to the victim organization demanding tens of thousands of dollars in Bitcoin for the safe return of said data.

Victims were typically told that if they refused to pay, the stolen data would be sold to cybercriminals lurking on Dark Web forums. Worse yet, TDO also promised to make sure the news media knew that victim organizations were more interested in keeping the breach private than in securing the privacy of their customers or patients.

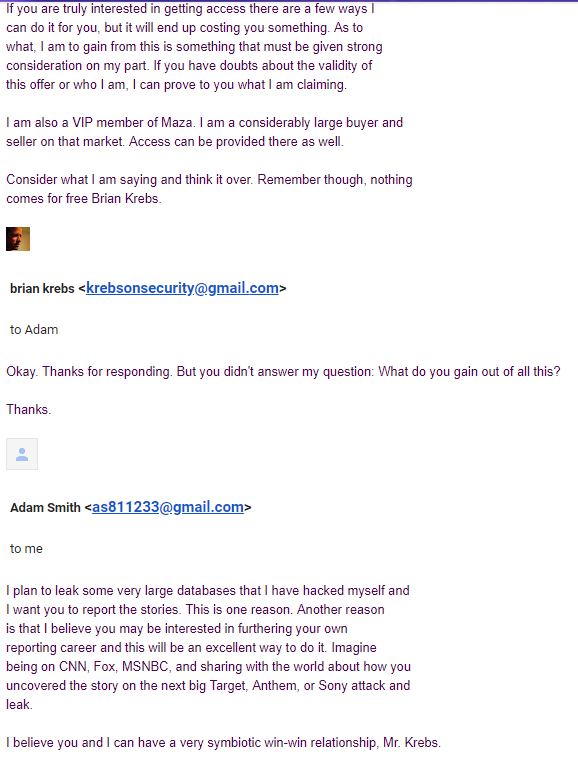

In fact, the apparent ringleader of TDO reached out to KrebsOnSecurity in May 2016 with a remarkable offer. Using the nickname “Arnie,” the public voice of TDO said he was offering exclusive access to news about their latest extortion targets.

Snippets from a long email conversation in May 2016 with a hacker who introduced himself as Adam but would later share his nickname as “Arnie” and disclose that he was a member of The Dark Overlord. In this conversation, he is offering to sell access to scoops about data breaches that he caused.

Arnie claimed he was an administrator or key member on several top Dark Web forums, and provided a handful of convincing clues to back up his claim. He told me he had real-time access to dozens of healthcare organizations they’d hacked into, and that each one which refused to give in to TDO’s extortion demands could turn into a juicy scoop for KrebsOnSecurity.

Arnie said he was coming to me first with the offer, but that he was planning to approach other journalists and news outlets if I declined. I balked after discovering that Arnie wasn’t offering this access for free: He wanted 10 bitcoin in exchange for exclusivity (at the time, his asking price was roughly equivalent to USD $5,000).

Perhaps other news outlets are accustomed to paying for scoops, but that is not something I would ever consider. And in any case the whole thing was starting to smell like a shakedown or scam. I declined the offer. It’s possible other news outlets or journalists did not; I will not speculate on this matter further, other than to say readers can draw their own conclusions based on the timeline and the public record.

WHO IS SOUNDCARD?

Fast-forward to September 2017, and Troia was contacting me almost daily to share tidbits of research into email addresses, phone numbers and other bits of data apparently tied to TDO’s communications with victims and their various identities on Dark Web forums.

His research was exhaustive and occasionally impressive, and for a while I caught the TDO bug and became engaged in a concurrent effort to learn the identities of the TDO members. For better or worse, the results of that research will have to wait for another story and another time.

At one point, Troia told me he’d gained acceptance on the Dark Web forum Kickass, using the hacker nickname “Soundcard“. He said he believed a presence on all of the forums TDO was active on was necessary for figuring out once and for all who was behind this brazen and very busy extortion group.

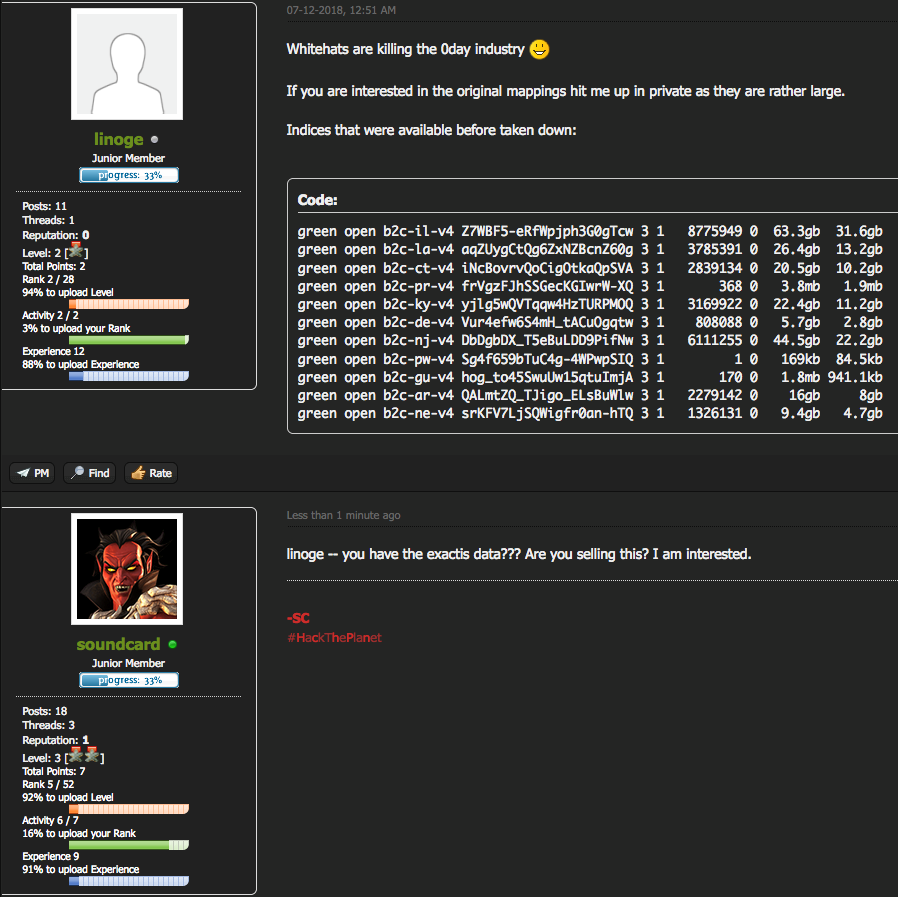

Here is a screen shot Troia shared with me of Soundcard’s posting there, which concerned a July 2018 forum discussion thread about a data leak of 340 million records from Florida-based marketing firm Exactis. As detailed by Wired.com in June 2018, Troia had discovered this huge cache of data unprotected and sitting wide open on a cloud server, and ultimately traced it back to Exactis.

After several weeks of comparing notes about TDO with Troia, I learned that he was telling random people that we were “working together,” and that he was throwing my name around to various security industry sources and friends as a way of gaining access to new sources of data.

I respectfully told Troia that this was not okay — that I never told people about our private conversations (or indeed that we spoke at all) — and I asked him to stop doing that. He apologized, said he didn’t understand he’d overstepped certain boundaries, and that it would never happen again.

But it would. Multiple times. Here’s one time that really stood out for me. Earlier this summer, Troia sent me a link to a database of truly staggering size — nearly 10 terabytes of data — that someone had left open to anyone via a cloud instance. Again, no authentication or password was needed to access the information.

At first glance, it appeared to be LinkedIn profile data. Working off that assumption, I began a hard target search of the database for specific LinkedIn profiles of important people. I first used the Web to locate the public LinkedIn profile pages for nearly all of the CEOs of the world’s top 20 largest companies, and then searched those profile names in the database that Troia had discovered.

Suddenly, I had the cell phone numbers, addresses, email addresses and other contact data for some of the most powerful people in the world. Immediately, I reached out to contacts at LinkedIn and Microsoft (which bought LinkedIn in 2016) and arranged a call to discuss the findings.

LinkedIn’s security team told me the data I was looking at was in fact an amalgamation of information scraped from LinkedIn and dozens of public sources, and being sold by the same firm that was doing the scraping and profile collating. LinkedIn declined to name that company, and it has not yet responded to follow-up questions about whether the company it was referring to was Apollo.

Sure enough, a closer inspection of the database revealed the presence of other public data sources, including startup web site AngelList, Facebook, Salesforce, Twitter, and Yelp, among others.

Several other trusted sources I approached with samples of data spliced from the nearly 10 TB trove of data Troia found in the cloud said they believed LinkedIn’s explanation, and that the data appeared to have been scraped off the public Internet from a variety of sources and combined into a single database.

I told Troia it didn’t look like the data came exclusively from LinkedIn, or at least wasn’t stolen from them, and that all indications suggested it was a collection of data scraped from public profiles. He seemed unconvinced.

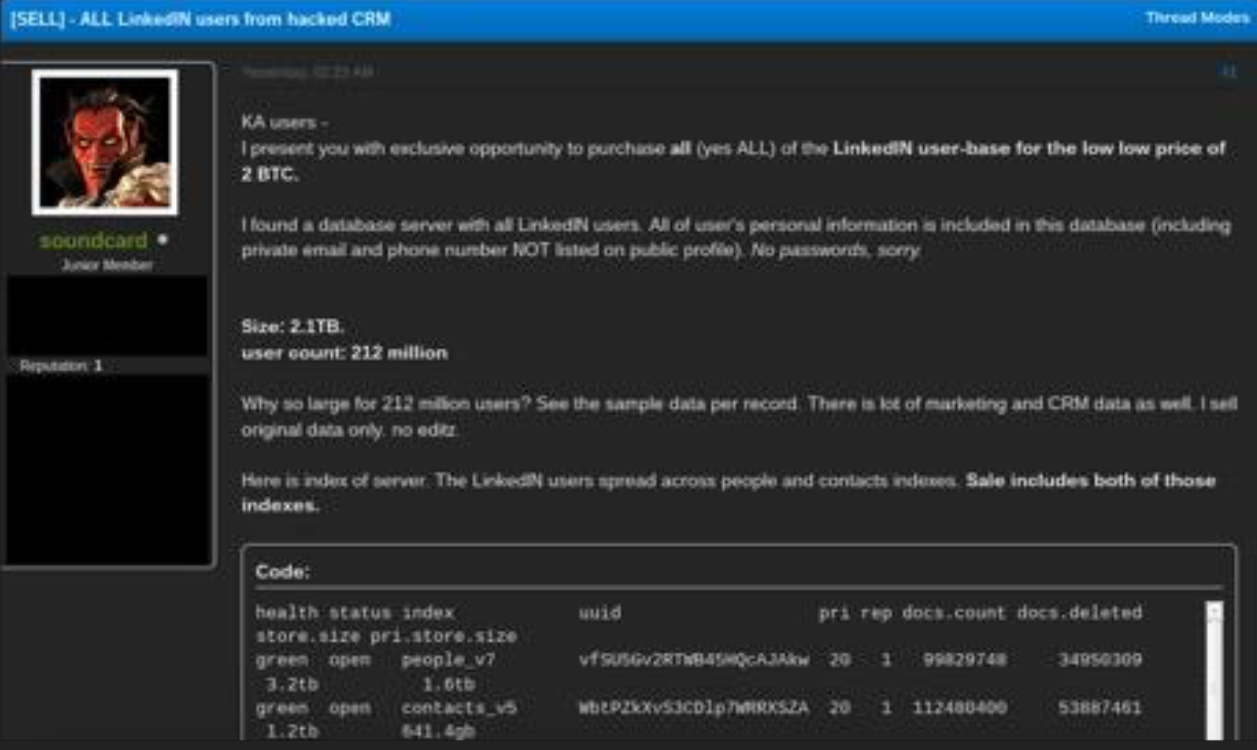

Several days after my second call with LinkedIn’s security team — around Aug. 15 — I was made aware of a sales posting on the Kickass crime forum by someone selling what they claimed was “all of the LinkedIN user-base.” The ad, a blurry, partial screenshot of which can be seen below, was posted by the Kickass user Soundcard. The text of the sales thread was as follows:

Soundcard, a.k.a. Troia, offering to sell what he claimed was all of LinkedIn’s user data, on the Dark Web forum Kickass.

“KA users –

I present you with exclusive opportunity to purchase all (yes ALL) of the LinkedIN user-base for the low low price of 2 BTC.

I found a database server with all LinkedIN users. All of user’s personal information is included in this database (including private email and phone number NOT listed on public profile). No passwords, sorry.

Size: 2.1TB.

user count: 212 million

Why so large for 212 million users? See the sample data per record. There is lot of marketing and CRM data as well. I sell original data only. no editz.

Here is index of server. The LinkedIN users spread across people and contacts indexes. Sale includes both of those indexes.

Questions, comments, purchase? DM me, or message me – soundcard@exploit[.]im

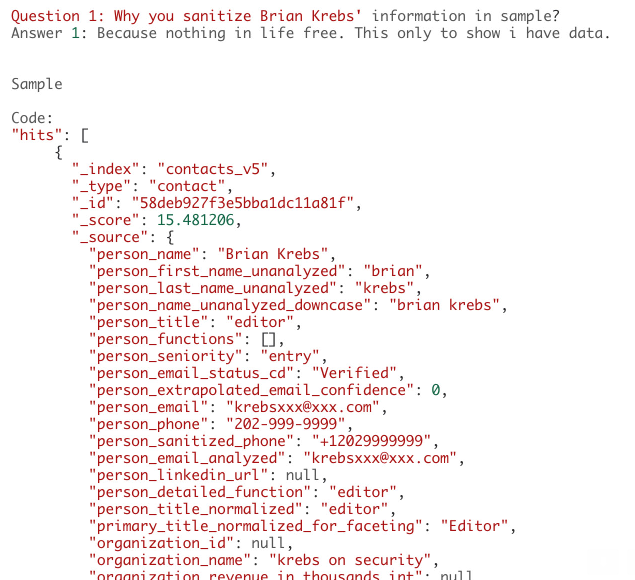

The “sample data” included in the sales thread was from my records in this huge database, although Soundcard said he had sanitized certain data elements from this snippet. He explained his reasoning for that in a short Q&A from his sales thread:

Question 1: Why you sanitize Brian Krebs’ information in sample?

Answer 1: Because nothing in life free. This only to show i have data.

I soon confronted Troia not only for offering to sell leaked data on the Dark Web, but also for once again throwing my name around in his various activities — despite past assurances that he would not. Also, his actions had boxed me into a corner: Any plans I had to credit him in a story for eventually helping to determine the source of the leaked data (which we now know to be Apollo) became more complicated without also explaining his Dark Web alter ego as Soundcard, and I am not in the habit of omitting such important details from stories.

Troia assured me that he never had any intention of selling the data, and that the whole thing had been a ruse to help smoke out some of the suspected TDO members.

For its part, LinkedIn’s security team was not amused, and published a short post to its media page denying that the company had suffered a security breach.

“We want our members to know that a recent claim of a LinkedIn data breach is not accurate,” the company wrote. “Our investigation into this claim found that a third-party sales intelligence company that is not associated with LinkedIn was compromised and exposed a large set of data aggregated from a number of social networks, websites, and the company’s own customers. It also included a limited set of publicly available data about LinkedIn members, such as profile URL, industry and number of connections. This was not a breach of LinkedIn.”

It is quite a fine line to walk when self-styled security researchers mimic cyber criminals in the name of making things more secure. On the one hand, reaching out to companies that are inadvertently exposing sensitive data and getting them to secure it or pull it offline altogether is a worthwhile and often thankless effort, and clearly many organizations still need a lot of help in this regard.

On the other hand, most organizations that fit this description simply lack the security maturity to tell the difference between someone trying to make the Internet a safer place and someone trying to sell them a product or service.

As a result, victim organizations tend to react with deep suspicion or even hostility to legitimate researchers and security journalists who alert them about a data breach or leak. And stunts like the ones described above tend to have the effect of deepening that suspicion, and sowing fear, uncertainty and doubt about the security industry as a whole.

Source: krebsonsecurity.com

Reviewed by Anonymous

on

4:57 PM

Rating:

Reviewed by Anonymous

on

4:57 PM

Rating: